This post is part of a broader conversation called The Shift, started by Dayton web design company Sparkbox. To read more posts in this series, browse the #startYourShift hashtag on Twitter. This month’s topic: how to make the web better.

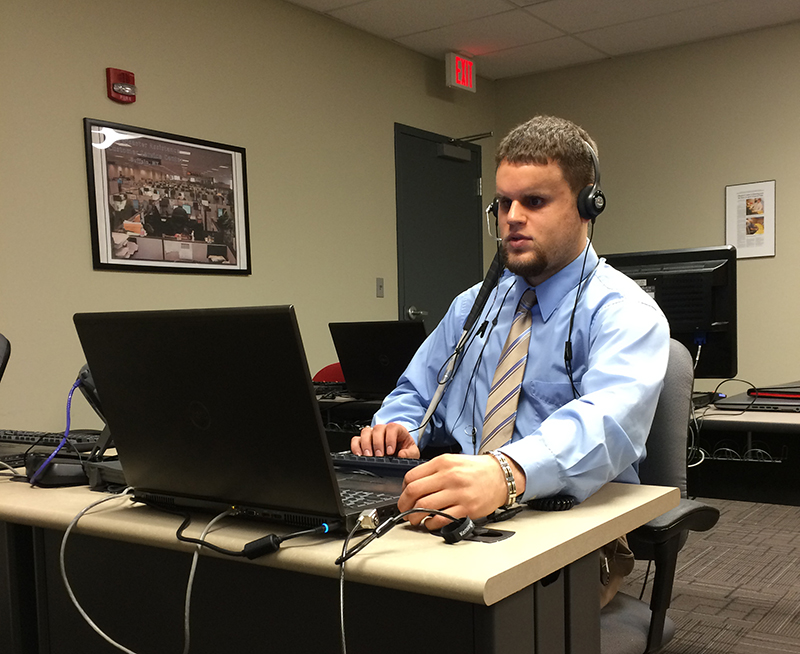

Raymond Zylinski, assistant AT (assistive technology) instructor at Buffalo’s Olmsted Center for Sight, shows me how to use YouTube. The computerized voice of JAWS (Job Access With Speech), his screen reader, lists off page elements as he selects them: first the edit field, where he searches for The Beatles, and then the search results, which he proceeds through until finally settling on “Penny Lane.”

Ray is blind, and YouTube is nominally an “accessible” website. He’s also really, really good with JAWS. So I’m surprised by what happens next: YouTube’s accessibility more or less falls apart. Skipping the five-minute ad before the video? Next to impossible with JAWS. Going fullscreen, a necessity for low-vision users? You can’t do it without clicking, despite the fact that the visually impaired use their keyboards exclusively to interact with web pages.

The worst part from my perspective is the labels. Blind users count on interactive elements on a page, such as buttons and fields, to be properly labeled so that they know how to interact with them. But the YouTube player is a mess of “unlabeled” buttons that rely entirely on visual cues for users to figure them out. I watch as Ray selects the unlabeled Vevo button overlaid on the video, which takes us to Vevo’s YouTube channel, which autoplays a video of Selena Gomez explaining which music videos were hot this week.

Ray Zylinski, assistant AT instructor at Olmsted Center for Sight, demonstrates how he uses JAWS to use his computer. Ray is blind.

Ray, of course, is doing this all for the sake of demonstration. He’s a JAWS power user who has been blind since he was a child: he’s developed plenty of “street smarts” (as his colleague I. Khan, a trainer at OCS’s Statler Center, calls them) for traversing a web that was designed for sighted users. We’re seated in OCS’s mobile computer lab, which he and Khan use to train visually impaired individuals on computer use. It’s a setup he’s familiar with.

He’s simply trying to show me the limits of designing for “accessibility.”

“By the term ‘accessibility,’ used lightly, YouTube is accessible,” Ray explains. “If I wanted to listen to ‘Penny Lane,’ it was playing… but there’s no usability to it.”

Accessibility vs. Usability in Web Design

The push for usability over accessibility is relatively recent.

“A few years ago we were happy if everything read on the screen,” says Khan. “Now we’re at the point where usability is the term. We’re kind of merging it with the whole concept of universal design.”

Most every web designer will tell you that they design with usability in mind for sighted and visually impaired users alike. But actually implementing and testing for usability the visually impaired has fallen behind the effort to create a more interesting, interactive web for the sighted.

508 Compliance: Good-Natured but Wrong-Headed

Part of the problem is the reliance on outdated, irrelevant technical standards derived from Section 508 of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973.

“What I like to tell companies when they mention they’re 508 compliant is that 508 compliance is for Congress and courtrooms and that’s about it,” says Khan. “Ask any JAWS user ‘How about that 508?’ Once they stop laughing, they’ll tell you that it doesn’t represent anything.”

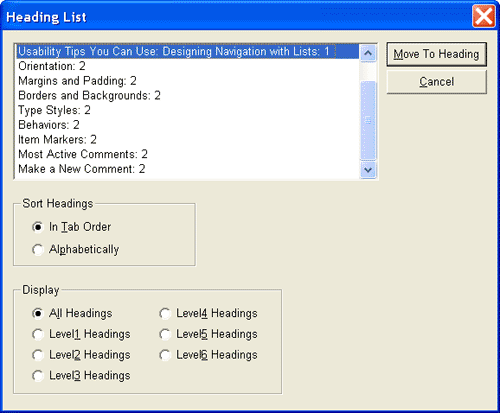

The JAWS interface, specifically the list of headings which a user can arrow through using their keyboard. Courtesy of Peachpit.

In Khan’s view, 508 is overly technical and agnostic of context. It focuses on whether certain elements like headings or ARIA regions exist instead of whether they make it easier for a visually impaired user to interact with a web page. He likens it to the federal government mandating that every page of a website have a banner scrolling across the top without giving any guidance as to what the banner says or what it should do.

“I don’t even like to call [508 requirements] bare bones,” says Khan.“They’re in a separate vein from what would be usable… they’re certainly necessary, but they need a supplement.”

Doing Usability Right with Human Testing

In order to supplement the demand for more automatic, yes-or-no 508 compliance checks, OCS now offers assistive technology consults to companies who want to do better. In the consults, expert JAWS users like Ray along with more novice users dig into a specific transaction or process on a website, making note of whatever obstacles the design might unwittingly put in the way of a visually impaired user. OCS also offers higher-level surveys, where 30 or 40 visually impaired individuals of varying skillsets test a website for usability, as well as manual 508 compliance checks.

These consults are far and away more useful than automated 508 compliance checks. Even sighted users with knowledge of the issues visually impaired individuals face on the web can’t audit their sites as effectively: eventually, visual cues will likely compromise the integrity of the attempt. As Khan says, “your eyes can be your worst enemy when testing for usability.”

“A design company wouldn’t show their site to two JAWS users to ask them how it visually looks,” says Khan. “But on the flip side, it’s two visual users making the determination of accessibility.”

Accessibility and usability, he points out, aren’t yes or no questions. Once you get past the dictates of 508 compliance, usability is determined as much as the taste and skill level of the user as by the technical elements on the page. That’s why integrating the human element into accessibility testing is so vital to making the web better for the visually impaired.

Learning Accessibility: Productively Uncomfortable

Learning to make accessibility a priority is a process that might push people out of their comfort zones. Brooke Kibrick, OCS’s marketing and events coordinator, recounts the learning experience she got the first time she edited the center’s website.

“Both of my parents are graphic designers,” says Kibrick. “I came from a company that spent thousands of dollars on making our website pretty. I came here and the first thing I put on our website, I get a call from Khan asking ‘What are you doing?’”

Learning experiences like that, or hearing that a stunning website is next-to-useless for a visually impaired user, might be difficult, but they’re necessary to start making things better.

The Value of a More Accessible Web

211: a Health & Human Service

“911 is the number you call when you have a burning house. 211 is the number you call when you have a burning question.”

That’s how Kibrick explains the value of 211, quoting one of her coworkers. If you’ve never called 211, here’s how it works: you dial 211 and you get connected to an operator who can help you with basically anything. Need public assistance? 211 can connect you to resources. Stuck in the kitchen on Thanksgiving with no idea how to prep a turkey? 211 can help with that, too.

What most people don’t realize about 211 is that, locally, it’s housed at the Olmsted Center for Sight, and that most of the operators are blind or visually impaired. Along with career training, OCS and its Statler Center provide employment through programs like their contact center. 211 isn’t their only client, but it’s their primary contract.

211 is a United Way-supported national program, but centers are staffed and run locally, like the 211 center at the Olmsted Center for Sight.

That means the operators in OCS’s call center have to be on their toes all the time. There’s no telling what the next call might entail.

The logistics of the process are where things get really impressive. Operators use dual-input headphones to take calls and operate their computers at the same time. Callers ask questions in one ear and JAWS reads their screens in the other. Imagining having to process both of those auditory streams simultaneously makes me feel dizzy. Ray explains how he does it in what Brooke and Khan playfully refer to as his “finale.”

“We talked about novice users and ace users [of JAWS],” says Ray. “What does that mean? Potentially, it’s keyboard awareness, computer awareness and what JAWS is doing. But there’s also a factor of speech rate.”

By dialing up JAWS’s speech rate, Ray can navigate information as quickly as he needs to in order to keep up with a caller. In fact, he can navigate it much more quickly than a sighted user could ever read it. Listen carefully below:

My jaw is dropped throughout the entire demonstration. I can’t imagine being able to understand JAWS at that high of a speech rate, much less with a caller in my other ear asking questions.

Examples like this expose the thought that hiring disabled individuals doesn’t make good business sense for what it is: a lazy, unethical lie.

Making Economic Sense of Accessibility

Data supports the claim that accessibility pays. In terms of job performance, disabled individuals perform as well or better than their peers. They tend to be more loyal, engaged employees who help to refine internal processes, easily outweighing the slight cost of accommodating their unique needs. In addition, if hiring disabled employees isn’t an outright federal requirement for a company, it can still lead to upwards of $20,000 in federal benefits and tax credits.

Despite the demonstrated value, under 18 percent of disabled individuals in the United States are employed, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Much of the responsibility certainly lies with employers who are still unwilling to invest in disabled individuals. But some also lies with the developers of resources and technology who also make the decision not to invest in disabled individuals, especially the visually impaired.

As digital technology becomes more integrated into our everyday lives, continuing to conceptualize accessibility as an added benefit or a technical requirement means actively excluding the visually impaired from the web. That means preventing these individuals from accessing vital resources and information, connecting with others and experiencing something that sighted users take for granted.

The economic value of accessibility is important: not only could it boost employment for the disabled, but it could boost the bottom line for business owners, who open up an entirely new market for their products when they make their web sites accessible to the visually impaired.

But economics pale far, far in comparison to the ethics. Considering the amount of resources out there on the subject, as well as the amount of people who are willing to help you to make the web more accessible, you’re either working on it or you’re discriminating for the sake of convenience. There’s not much in between.

A Note on LUMINUS & Accessibility

We know we aren’t perfect on accessibility and we aren’t trying to say that we are. But we want to be better and we welcome any criticism or suggestions that might help us to achieve that goal.

WATCH: How the Olmsted Center for Sight’s Statler Center Helped One Graduate Regain His Independence

RESOURCES

The Olmsted Center for Sight

The home page for The Olmsted Center for Sight.

WebAIM

A great place to start learning about web accessibility.

The A11Y Project

A collaborative effort by web developers to make designing for web accessibility “digestible,” “up-to-date” and “forgiving.”