Black Friday is easy to hate for a variety of concrete and abstract reasons.

On one hand, it’s a false consumerist holiday add-on that forces underpaid retail workers to labor Herculean hours so that folks who aren’t savvy enough to use the internet can get slight discounts on electronics already on the cusp of planned obsolescence.

On the other hand, it’s a cipher for all the things we feel guilty about pleasurably participating in: materialism, bargain hunting, camping outside of our local Target.

Despite or perhaps because of these mythic associations, the notoriety of Black Friday has far outgrown actual participation in the shopping event. Think with Google just released some tasty facts about the general public’s participation with Black Friday, and they might surprise you:

In-store and online shopping experiences are separate.

“Consumers are turning to their phones in hundreds of micro-moments” throughout the shopping experience, says Google. Micro-moments are “when people reflexively turn to a device—increasingly a smartphone—to act on a need to learn something, do something, discover something, watch something, or buy something.”

Basically, the near-seamless integration of wireless internet into our daily lives has enabled us to realize these types of desires almost immediately, wherever we are. Google estimates that 82 percent of smartphone users consult their phones in-store.

For retailers, this means that the Black Friday shopping experience has become much more than releasing an ad and watching throngs of would-be savers gather at your automatic doors.

Say you’re selling a 32-inch Samsung flatscreen for $179.99. The savvy shopper doesn’t simply pick up the box because they noticed that you’ve knocked 30 bucks off your standard price. They take to their smartphones and Google prices for the same TV at competing retailers. They might even post to social media asking for advice from their network on their shopping decision (that’s what I recently did, and I got the same TV for 100 bucks from a friend).

The takeaway: getting shoppers into your store is not the end of your selling journey. It’s probably not the beginning, either. Most people shopping on Black Friday have probably spent plenty of time already researching you and your competitors and will likely continue that research process the entire time they’re in your store.

While some people do treat Black Friday like a sport, it’s highly unlikely that anyone will be huddled at the front entrance of your store, frothing at the mouth with a fistful of cash to immediately spend on the best deal they come across.

People start shopping in the wee hours of the morning.

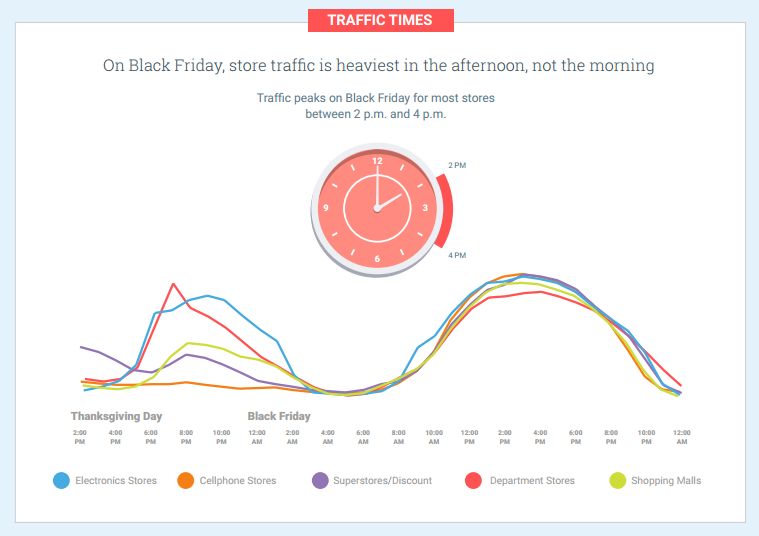

Not really. Actually, it’s the opposite. As anyone who has ever owned an alarm clock will tell you, people like to sleep, especially after gorging themselves on turkey and wine. Here’s Google’s graph:

Across all types of stores, the hours between 2:00 AM and 8:00 AM actually have the lowest volume of shoppers (though, likely, they have the highest ratio of wild-eyed, bargain-crazy viral-videos-waiting-to-happen). Shopping picks up at sensible times for people have are off work but have hangovers, peaking between 2:00 PM and 4:00 PM.

Black Friday is the “Biggest Shopping Day of the Year.”

Think about this one for a second: who do you know that actually gets their holiday shopping done that early?

The myth that Black Friday represents the peak of retailing is a self-serving myth fueled by the retailers themselves. It’s probably more useful in kick-starting people’s shame spirals at putting off their holiday shopping than actually getting people out to shop on November 27.

As Google found, the busiest time of year for most retailers is the last Saturday before Christmas:

If you ever needed hard data that everyone procrastinates as much as you do, here it is.

The notable outliers here are cellphone stores and electronics stores, which actually do see their volumes peak on Black Friday. But that’s likely because those are the stores offering the most significant deals on high-price items (compare the dollar stores, which see consistent volume throughout the holiday season).

To make a sweeping generalization: Black Friday is as made up as you think it is. Dealnews actually found that if you’re hungrier for savings than family bonding and tryptophan, shopping on Thanksgiving Day actually yields better deals and less of a chance you’ll get trampled to death.

If nobody likes Black Friday and people don’t really participate how we think they do, why does it still exist? Because it’s a useful symbol.

For one thing, it jumpstarts the holiday shopping season: even if you don’t go shopping on Black Friday, you’re still acutely aware that the games have begun.

On the other hand, it functions as a scapegoat for the entirety of our holiday shopping experience. We might feel a vague guilt over spending countless hours bargain hunting only to drop $200 on something no one really needs, but at least we can comfort ourselves that we aren’t those people: the imagined hordes of discount shoppers who trade a piece of their humanity for a doorbuster.